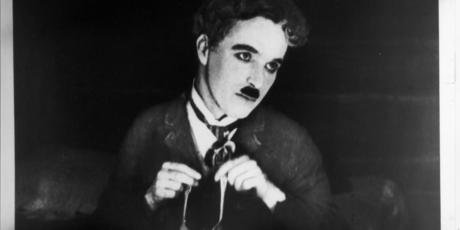

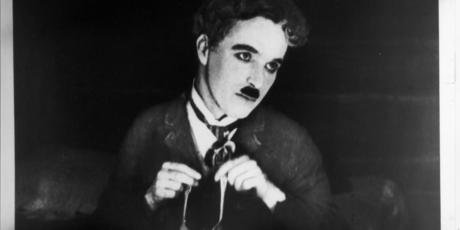

The Kid (1921)

The kid in which he introduced to the screen one of the greatest child actors the world has ever known - Jackie Coogan. The next year, he produced "The Idle Class", in which he portrayed a dual character.

Then, feeling the need of a complete rest from his motion picture activities, Chaplin sailed for Europe in September 1921. London, Paris, Berlin and other capitals on the continent gave him tumultuous receptions. After an extended vacation, Chaplin returned to Hollywood to resume his picture work and start his active association with United Artists.

Under his arrangement with U.A., Chaplin made eight pictures, each of feature length, in the following order:

The Masterpiece Features

(Notice : the comments on each films are taken from the articles of David Robinson which we strongly recommend to read by followoing the link since they have many more insites on his life)A Woman of Paris (1923)

was a courageous step in the career of Charles Chaplin. After seventy films in which he himself had appeared in every scene, he now directed a picture in which he merely walked on for a few seconds as an unbilled and unrecognisable extra – a porter at a railroad station. Until this time, every film had been a comedy. A Woman of Paris was a romantic drama. This was not a sudden impulse. For a long time Chaplin had wanted to try his hand at directing a serious film. In the end, the inspiration for A Woman of Paris came from three women. First was Edna Purviance, who had been his ideal partner in more than 35 films. Now, though, he felt that Edna was growing too mature for comedy, and decided to make a film that would launch her on a new career as a dramatic actress.

The Gold Rush (1925)

Chaplin generally strove to separate his work from his private life; but in this case the two became inextricably and painfully mixed.

Searching for a new leading lady, he rediscovered Lillita MacMurray, whom he had employed, as a pretty 12-year-old, in

The Kid Still not yet sixteen, Lillita was put under contract and re-named Lita Grey.

Chaplin quickly embarked on a clandestine affair with her; and when the film was six months into shooting, Lita discovered she was pregnant. Chaplin found himself forced into a marriage which brought misery to both partners, though it produced two sons, Charles Jr and Sydney Chaplin.

The Circus (1928)

"The Circus" won Charles Chaplin his first Academy Award – it was still not yet called the ‘Oscar’ – he was given it at the first presentations ceremony, in 1929. But as late as 1964, it seemed, this was a film he preferred to forget. The reason was not the film itself, but the deeply fraught circumstances surrounding its making.

Chaplin was in the throes of the break-up of his marriage with Lita Grey; and production of The Circus coincided with one of the most unseemly and sensational divorces of twenties Hollywood, as Lita’s lawyers sought every means to ruin Chaplin’s career by smearing his reputation.

As if his domestic troubles were not enough, the film seemed fated to catastrophe of every kind [...]

In the late 1960s, after the years spent trying to forget it, Chaplin returned to "The Circus" to re-release it with a new musical score of his own composition. [...] It seemed to symbolize his reconciliation to the film which cost him so much stress.

"City Lights" proved to be the hardest and longest undertaking of Chaplin’s career. By the time it was completed he had spent two years and eight months on the work, with almost 190 days of actual shooting. The marvel is that the finished film betrays nothing of this effort and anxiety. Even before he began City Lights the sound film was firmly established.

This new revolution was a bigger challenge to Chaplin than to other silent stars. His Tramp character was universal. His mime was understood in every part of the world. But if the Tramp now began to speak in English, that world-wide audience would instantly shrink.

Chaplin boldly solved the problem by ignoring speech, and making City Lights in the way he had always worked before, as a silent film. However he astounded the press and the public by composing the entire score for "City Lights".

The premieres were among the most brilliant the cinema had ever seen. In Los Angeles, Chaplin’s guest was Albert Einstein; while in London Bernard Shaw sat beside him. "City Lights" was a critical triumph. All Chaplin’s struggles and anxieties, it seemed, were compensated by the film which still appears as the zenith of his achievement and reputation.

Modern Times (1936)

Chaplin was acutely preoccupied with the social and economic problems of this new age. In 1931 and 1932 he had left Hollywood behind, to embark on an 18-month world tour. In Europe, he had been disturbed to see the rise of nationalism and the social effects of the Depression, of unemployment and of automation.

He read books on economic theory; and devised his own Economic Solution, an intelligent exercise in utopian idealism, based on a more equitable distribution not just of wealth but of work.

In 1931 he told a newspaper interviewer, “Unemployment is the vital question . . . Machinery should benefit mankind. It should not spell tragedy and throw it out of work”.

The Great Dictator (1940)

When writing "The Great Dictator" in 1939, Chaplin was as famous worldwide as Hitler, and his Tramp character wore the same moustache. He decided to pit his celebrity and humour against the dictator’s own celebrity and evil. He benefited – if that is the right word for it, given the times – from his “reputation” as a Jew, which he was not – (he said “I do not have that pleasure”).

In the film Chaplin plays a dual role –a Jewish barber who lost his memory in a plane accident in the first war, and spent years in hospital before being discharged into an antisemite country that he does not understand, and Hynkel, the dictator leader of Ptomania, whose armies are the forces of the Double Cross, and who will do anything along those lines to increase his possibilities for becoming emperor of the world. Chaplin’s aim is obvious, and the film ends with a now famous and humanitarian speech made by the barber, "speaking Chaplin’s own words":/en/articles/29 .

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

The idea was originally suggested by Orson Welles, as a project for a dramatised documentary on the career of the legendary French murder Henri Désiré Landru – who was executed in 1922, having murdered at least ten women, two dogs and one boy.

Chaplin was so intrigued by the idea that he paid Welles $5000 for it. The agreement was signed in 1941, but Chaplin took four more years to complete the script. In the meantime the irritating distractions of a much-publicised and ugly paternity suit had been compensated by his brilliantly successful marriage to Oona O’Neill.

In the late 1940s, America¹s Cold War paranoia reached its peak, and Chaplin, as a foreigner with liberal and humanist sympathies, was a prime target for political witch-hunters. This was the start of Chaplin’s last and unhappiest period in the United States, which he was definitively to leave in 1952.

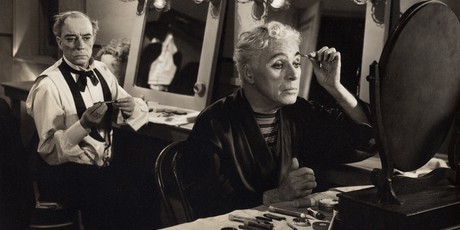

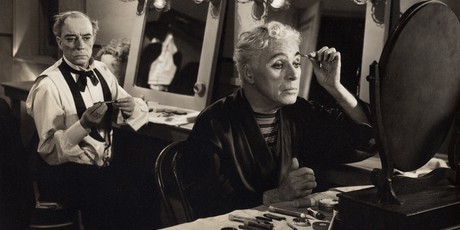

Limelight (1952)

Not surprisingly, then, in choosing his next subject he deliberately sought escape from disagreeable contemporary reality. He found it in bitter-sweet nostalgia for the world of his youth – the world of the London music halls at the opening of the 20th century, where he had first discovered his genius as an entertainer.

With this strong underlay of nostalgia, Chaplin was at pains to evoke as accurately as possible the London he remembered from half a century before and it is clear from the preparatory notes for the film that the character of Calvero had a very similar childhood to Chaplin’s own. Limelight's story of a once famous music hall artist whom nobody finds amusing any longer may well have been similarly autobiographical as a sort of nightmare scenario.

Chaplin’s son Sydney plays the young, talented pianist who vies with Calvero for the young ballerina’s heart, and several other Chaplin family members participated in the film. It was when on the boat travelling with his family to the London premiere of

Limelight that Chaplin learned that his re-entry pass to the United States had been rescinded based on allegations regarding his morals and politics.

Chaplin therefore remained in Europe, and settled with his family at the Manoir de Ban in Corsier sur Vevey, Switzerland, with view of lake and mountains. What a difference from California. He and Oona went on to have four more children, making a total of eight.

A King in New York

With A King in New York Charles Chaplin was the first film-maker to dare to expose, through satire and ridicule, the paranoia and political intolerance which overtook the United States in the Cold War years of the 1940s and 50s. Chaplin himself had bitter personal experience of the American malaise of that time. [...]

To take up film making again, as an exile, was a challenging undertaking. He was now nearing 70. For almost forty years he had enjoyed the luxury of his own studio and a staff of regular employees, who understood his way of work. Now though he had to work with strangers, in costly and unfriendly rented studios. [...] The film shows the strain.

In 1966 he produced his last picture, “A Countess from Hong Kong” for Universal Pictures, his only film in colour, starring Sophia Loren and Marlon Brando. The film started as a project called Stowaway in the 1930s, planned for Paulette Goddard. Chaplin appears briefly as a ship steward, Sydney once again has an important role, and three of his daughters have small parts in the film. The film was unsuccessful at the box office, but Petula Clark had one or two hit records with songs from the soundtrack music and the music continues to be very popular.

HOLOCAUST FORESHADOWED

HOLOCAUST FORESHADOWED Hitler labeled Chaplin a "Jew." Chaplin never denied it, although he was not Jewish. Chaplin was part Rom on his mother's side and was proud of it. However, Chaplin

Hitler labeled Chaplin a "Jew." Chaplin never denied it, although he was not Jewish. Chaplin was part Rom on his mother's side and was proud of it. However, Chaplin